"There are decades where nothing happens and there are weeks where decades happen"

- Lenin

On the outskirts of Cairo, the government has an ambitious plan to build a new capital. A sprawling landscape of half-constructed condos and skyscrapers - a competition between concrete and desert. The large billboards milestoned along the motorway advertising luxury compounds, shopping centres and corporate headquarters; New Cairo... coming soon.

The American University in Cairo hosted the annual Tällberg Conference this year and I was honoured to have been invited as a part of this unique delegation of participants. With the AUC's impressive new campus situated in New Cairo, we gathered in the imagined future of an ancient civilisation.

The Tällberg Foundation, launched in 1981, exists to provoke thinking—and action based on thinking— about the issues that are challenging the evolution of liberal democracies. Their annual conference converges with a different theme every year, and in a different part of the world to reflect the global nature of the issues discussed.

AUC New Cairo Campus

A graphic of the new Egyptian capital shows completed residential districts, as well as the planned tallest building in Africa at 345 metres high. Photograph: ACUD

This year's theme was "Leadership in a Disrupted World". Alan Stoga, Chairman of the board of the Tällberg Foundation summed up the spirit of this workshop in these lines from the American poet Howard Nemerov, in Magnitudes:

"We stand now in the place and limit of time

Where hardest knowledge is turning into dream,

And nightmares still contained in sleeping dark

Seem on the point of bringing into day

The sweating panic that starts the sleeper up.

One or another nightmare may come true,

And what to do then? What in the world to do?

That is the challenge we face: What in the world to do?"

He then raises the question: "that is the challenge we face: What in the world to do?" - the magnitude of this question felt as impossible as the pyramids that stood across the river in Giza.

On the first day of the 2-day gathering, Alan Stoga started off with a presentation providing an overview of the current global dynamics. Nabil Fahmy (Dean of the School of Global Affairs and Public Policy at the AUC, former Egyptian Diplomat and Politician) followed up with an overview of the regional dynamics in the Middle East.

Alan and Nabil pieced together a strong narrative of the contemporary world by examining the interdependent effects of climate change, ideological polarisation, dwindling resources, shifting political centres, and disruptive technological advancements. With both speakers warning that the pace at which this is all taking place means that policy and regulations are unable to keep up.

By the end of this first session, the room felt heavy with the long list of challenges we faced. Various participants from environmental activists to diplomats commented on the topics covered with their own experience, expertise, and projections.

You could almost hear a collective sigh, when another hand shot up and Marwa el Dal (Founder and Chair of Waqfeyat al Maadi Community Foundation) asked why we are all being so cynical... yes, there are a lot of challenges but I also think there has been a lot of progress.

Laughter broke out and the dichotomy between pessimism and optimism set the tone for the rest of the conference.

WHY HERE?

When attending any conference/event, I find it to be imperative to examine Why. Time is the most valuable currency we own, and the question "why I'm I here?" underpins every decision I make about how I spend that currency.

Why are we here? Why are time and resources being allocated for this purpose?

Is there a purpose? What are the expected outputs? Is there an agreed objective or goal that can be met?

Working with communities living in conflict is a reminder every day that we need to act.

I was curious to see how this esteemed group of philanthropists, diplomats, politicians, activists, artists, magician, VCs, and entrepreneurs will come together to tackle the "doing" needed to be done.

During my time in Cairo, I was invited to be an active facilitator as well as an engaged participator.

I was surprised by the intensity of the discourse as well as the variety of attendees. What was refreshing about this conference was the unabashedly diverse selection of individuals. Seldom are there spaces created (physically or virtually) where you can intimately and openly talk about your collective fears whilst knowing that everyone has the equity and willingness to do something about them.

It was equally welcoming during the course of the conference to hear people speak honestly about the limitations of their circumstances; be it money, bureaucratic red tape, political party lines, or social constraints.

Most of us find it difficult to be vulnerable, especially in a professional context, it often feels inappropriate and almost damaging to be so. But it occurred to me that when you are honest about where you can't deliver, you can then openly help others to step in. Time and time again, it is obvious that without collaboration we cannot achieve any meaningful progress towards solving the issues in our disruptive world. This point could not have been any more apparent than in the Mass Migration panel I moderated on the last day of the conference.

The Mass Migration panel ignited a heated debate as the speakers were amazingly gracious with their honesty and transparency, The panel was curated so that there was an even split between the European and Middle Eastern perspectives. Two of the speakers Dilsa Demirbag-Sten and Rasmus Brygger are based in Scandinavia, whilst the other two speakers Dr. Ibrahim Awad and Helen van Wengen are living and working in the Middle East. The initial debate began with some back and forth around rhetorics that we see in the media - is the current migration situation a crisis or just a natural flow of human history? But it soon transpired that we can all agreed on the fact that this is a crisis of our time. However, the panel felt the need to reject the term in the way that it’s touted by the European press as inflated and unjustified.

The number of refugees in Jordan, Lebanon, and Egypt for example, far outweigh the number of refugees in Europe. Yet we tend to hear the most grievances from European nations. The danger is when the transition countries become the destination countries. To a large extent that has already happened, but the strain it’s placing in these regions is becoming unbearable, and if the camel’s back does break, it’s going to destabilise the entire world.

Still, the wealthier nations of the Global North are not willing to look at the problem as a whole, but in pieces… eventually, they will have to realise that when the dam breaks, everyone’s going to run out of air. We are in it together.

ACTIVISM & YOUTH

The Egyptian novelist Youssef Rakah and I examined the nature of activism in an afternoon session, with Youssef discussing his experience of the Arab Spring and the events in Tahrir Square.

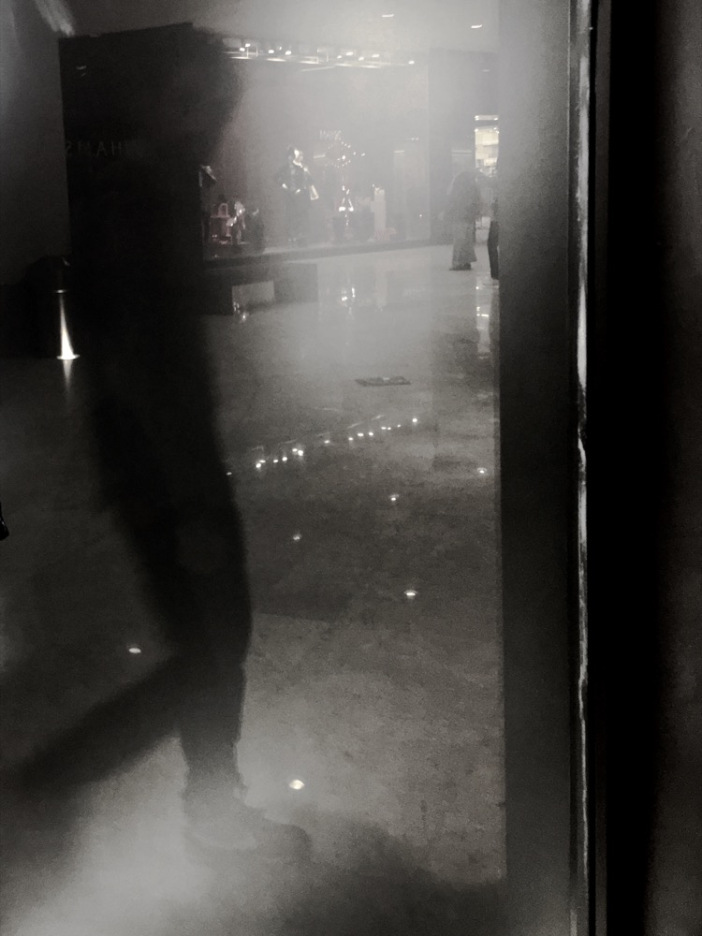

In his recounting of that time, Youssef remembered taking his camera and going out to demonstrate on Friday, January 28:

"Unlike the majority of “Arab Spring revolutionaries”, from the moment Tahrir Square was occupied in the small hours of Saturday, January 29 and until the long-time president Hosni Mubarak stepped down, I felt that I couldn’t photograph and protest at the same time, that to be photographing would render my presence in the protests insincere and that the protests were about more important things than photography...

Much later, while the aftermath of regime change made developments look more like an affliction and less like a triumph as the revolution was summarily betrayed – first by the rise of political Islam, then by a reinstatement of military despotism – I reencountered those loose archetypes once again, now no longer behaving with the urgency of historical players but simply going about their day...

While Egyptians themselves seemed to lose all connection with the excitement and hope and sheer living energy of early 2011, the characters of the revolution, it seemed to me, were hiding in the two-dimensional world of these surfaces…I like to think of them as leaves from a book of narrative poetry or lyrical storytelling which, on the all but opaque surfaces of daily life, trace the residue of a by now unequivocally lost revolution."

Tahrir Square, 2011.

Youssef spoke passionately and poignantly about the Arba Spring in Egypt. He admitted to his disillusionment since then, and spoke out about his disappointment in the lack of a united front during the uprising, and the way that young people were being misguided by false information as well as their own naivety.

Then a member of the delegation asked how we can help young people not to sacrifice themselves in vain for causes, people spoke about tempering the youths and giving them more time to learn how the world operates.

The room seem to concur with the premise of the question. However, as a millennial, I felt that I had to disagree with the idea that young people are necessarily naive and needed more time before they could lead. It is clear from our history that young people are at the core of driving movements which change the world. Even today, it is the young people who are demanding more social and moral responsibility from their politicians to their choice of clothing to their investments. They are not slow to put their money where their mouth is, and in the neoliberal world we live in, these choices propel change.

Copy Right: Youssef Rakha

Copy Right: Youssef Rakha

Copy Right: Youssef Rakha

I argued that young people are not naive simply because they dare to be unreasonable about what can be changed. The unencumbered courage that so often accompanies youth is what is required to change the game by breaking all the rules we think we ought to follow.

Looking around, I see young leaders who are ready now, who are doing now. But their growth is stunted and their efforts thwarted because they are not the ones in control of the resources.

What young people need is a seat at the table, and for those who have the agency to exercise power to invite them to collaborate.

We also cannot undermine the relationship between activism, youth, and social media. We only have to start by looking at the role social media had to play in all the major uprisings in recent memory:

The Arab Spring was notably catapulted and organised via Facebook

The Yellow Umbrella movement was co-ordinated through ad hoc apps that circumvented the government's attempts to intercept communication

In Turkey, the protesters live-streamed their march on Facebook and Periscope whilst Erdogan used Facebook Live to call out his supporters to the streets and eventually quelled the call for his resignation

In the Egyptian example, the 2011 revolution and the zeal for revolt has dissipated for now. But with over half of its population is under 35, if this majority doesn't have a major stake at the table, you can be sure that they will try, try again to topple the table.

After the discussion, a young congresswoman from the Kenyan delegation approached me to tell me how she's facing a constant uphill battle in her work: "Being 27 and a woman, people don't want to listen to you... they tell you that you're too young and don't know what you're talking about." Even though she was elected to office by the people, her voice is still delegitimised by the establishment. But she laughed it off with a shrug as if to say, that's fine, I am not going anywhere.